El

Dorado (English: “the golden one”) is the name of a Muisca tribal chief who

covered himself with gold dust and, as an initiation rite, dove into a highland

lake. Later it became the name of a legendary “Lost City of Gold”, which

fascinated explorers since the days of the Spanish Conquistadors. No evidence

for its existence has been found.

Imagined

as a place, El Dorado became a kingdom, an empire, and the city of this

legendary golden king. In pursuit of the legend, Francisco Orellana and Gonzalo

Pizarro departed from Quito in 1541 in a famous and disastrous expedition

towards the Amazon Basin, as a result of which Orellana became the first person

known to navigate the Amazon River all the way to its mouth.

The

original narrative is to be found in the rambling chronicle, El Carnero, of Juan

Rodriguez Freyle. According to Freyle, the king or chief priest of the Muisca

was said to be ritually covered with gold dust at a religious festival held in

Lake Guatavita, near present-day Bogotá Colombia.

In

1638 Juan Rodriguez Troxell wrote this account, addressed to the cacique or

governor of Guatavita:

The

ceremony took place on the appointment of a new ruler. Before taking office, he

spent some time secluded in a cave, without women, forbidden to eat salt, or to

go out during

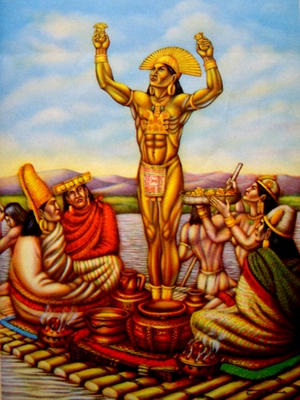

Depiction

of the Legend of El Dorado,

published in El Museo del Oro, 1923-1948

daylight.

The first journey he had to make was to go to the great lagoon of Guatavita, to

make offerings and sacrifices to the demon, which they worshipped as their god

and lord. During the ceremony, which took place at the lagoon, they made a raft

of rushes, embellishing and decorating it with the most attractive things they

had. They put on it four lighted braziers in which they burned much moque, which

is the incense of these natives, and also resin and many other perfumes. The

lagoon was large and deep, so that a ship with high sides could sail on it, all

loaded with an infinity of men and women dressed in fine plumes, golden plaques

and crowns... As soon as those on the raft began to burn incense, they also lit

braziers on the shore, so that the smoke hid the light of day. At this time they

stripped the heir to his skin, and anointed him with a sticky earth on which

they placed gold dust so that he was completely covered with this metal. They

placed him on the raft... and at his feet they placed a great heap of gold and

emeralds for him to offer to his god. In the raft with him went four principal

subject chiefs, decked in plumes, crowns, bracelets, pendants and ear rings all

of gold. They, too, were naked, and each one carried his offering... when the

raft reached the center of the lagoon, they raised a banner as a signal for

silence. The gilded Indian then... [threw] out all the pile of gold into the

middle of the lake, and the chiefs who had accompanied him did the same on their

own accounts... After this they lowered the flag, which had remained up during

the whole time of offering, and, as the raft moved towards the shore, the

shouting began again, with pipes, flutes, and large teams of singers and

dancers. With this ceremony the new ruler was received, and was recognized as

lord and king.

The

Muisca towns and their treasures quickly fell to the conquistadores. Taking

stock of their newly won territory, the Spaniards realized that — in spite of

the quantity of gold in the hands of the Indians — there were no golden

cities, nor even rich mines, since the Muiscas obtained all their gold in trade.

But at the same time, the Spanish began to hear stories of El Dorado from

captured Indians, and of the rites that used to take place at the lagoon of

Guatavita.

El

Dorado is applied to a legendary story in which precious stones were found in

fabulous abundance along with gold coins. The concept of El Dorado underwent

several transformations, and eventually accounts of the previous myth were also

combined with those of the legendary city. The resulting El Dorado enticed

European explorers for two centuries.

Among

the earliest stories was the one told by Diego de Ordaz’s lieutenant Martinez,

who claimed to have been rescued from shipwreck, conveyed inland, and

entertained by “El Dorado” himself (1531). During the Klein-Venedig period

in Venezuela (1528 - 1546), agents of the Welser banking family (which had

received a concession from Charles I of Spain) launched repeated expeditions

into the interior of the country in search of El Dorado.

In

1540 Gonzalo Pizarro, the younger half-brother of Francisco Pizarro, was made

the governor of the provenance of Quito in northern Ecuador. Shortly after

taking lead in Quito, Gonzalo learned from many of the natives of a valley far

to the east rich in both cinnamon and gold. He banded together 340 soldiers and

about 4000 natives in 1541 and led them eastward down the Rio Coca and Rio Napo.

Francisco de Orellana, Gonzalo’s nephew, accompanied his uncle on this

expedition. Gonzalo quit after many of the soldiers and natives had died from

hunger, disease, and periodic attacks by hostile natives. He ordered Orellana to

continue downstream, where he eventually made it to the Atlantic Ocean,

discovering the Amazon (named Amazon because of a tribe of female warriors that

attacked Orellana’s men while on their voyage.)

Other

expeditions include that of Philipp von Hutten (1541–1545), who led an

exploring party from Coro on the coast of Venezuela; and of Gonzalo Jiménez de

Quesada, the Governor of El Dorado, who started from Bogotá (1569).

Sir

Walter Raleigh, who resumed the search in 1595, described El Dorado as a city on

Lake Parime far up the Orinoco River in Guyana. This city on the lake was marked

on English and other maps until its existence was disproved by Alexander von

Humboldt during his Latin-America expedition (1799–1804).

In the mythology of the Muisca today, gold (Mnya) represents the energy contained in the trinity of Chiminigagua, which constitutes the creative power of everything that exists. Chiminigagua is, along with Bachué, Cuza, Chibchachum, Bochica, and Nemcatacoa, one of the creators of the universe.