Kraken

are mythical sea monsters of gargantuan size, said to have dwelt off the

coasts of Norway and Iceland. The sheer size and fearsome appearance

attributed to the beasts have made them common ocean-dwelling monsters in

various fictional works. The legend may actually have originated from

sightings of real giant squid that are variously estimated to grow to

13–15 m (40–50 ft) in length, including the tentacles. These creatures

normally live at great depths, but have been sighted at the surface and

reportedly have “attacked” ships.

Kraken

is the definite article form of krake, a Scandinavian word designating an

unhealthy animal, or something twisted. In modern German, Krake (plural and

declined singular: Kraken) means octopus, but can also refer to the

legendary Kraken.

Even though the name kraken never appears in the Norse sagas, there are similar sea monsters, the hafgufa and lyngbakr, both described in Örvar-Odds saga as a giant spider-creature. Carolus Linnaeus included kraken as cephalopods with the scientific name Microcosmus in the first edition of his Systema Naturae (1735), a taxonomic classification of living organisms, but excluded the animal in later editions. Kraken were also extensively described

by

Erik

Pontoppidan, bishop of Bergen, in his “Natural History of Norway”

(Copenhagen, 1752–3). Early accounts, including Pontoppidan’s, describe

the kraken as an animal “the size of a floating island” whose real

danger for sailors was not the creature itself, but the whirlpool it created

after quickly descending back into the ocean. However, Pontoppidan also

described the destructive potential of the giant beast: “It is said that

if it grabbed the largest warship, it could manage to pull it down to the

bottom of the ocean” (Sjögren, 1980). Kraken were always distinct from

sea serpents, also common in Scandinavian lore (Jörmungandr for instance).

According

to Pontoppidan, Norwegian fishermen often took the risk of trying to fish

over kraken, since the catch was so good. If a fisherman had an unusually

good catch, they used to say to each other, “You must have fished on

Kraken.” Pontoppidan also claimed that the monster was sometimes mistaken

for an island, and that some maps that included islands that were only

sometimes visible were actually indicating kraken. Pontoppidan also proposed

that a young specimen of the monster once died and was washed ashore at

Alstahaug (Bengt Sjögren, 1980).

Since

the late 18th century, kraken have been depicted in a number of ways,

primarily as large octopus-like creatures, and it has often been alleged

that Pontoppidan’s kraken might have been based on sailors’ observations

of the giant squid. In the earliest descriptions, however, the creatures

were more crab- like than octopus-like, and generally possessed traits that

are associated with large whales rather than with giant squid. Some traits

of kraken resemble undersea volcanic activity occurring in the Iceland

region, including bubbles of water; sudden, dangerous currents; and

appearance of new islets.

In

1802, the French malacologist Pierre Dénys de Montfort recognized the

existence of two kinds of giant octopus in Histoire Naturelle Générale et

Particuličre des Mollusques, an encyclopedic description of mollusks.

Montfort claimed that the first type, the kraken octopus, had been described

by Norwegian sailors and American whalers, as well as ancient writers such

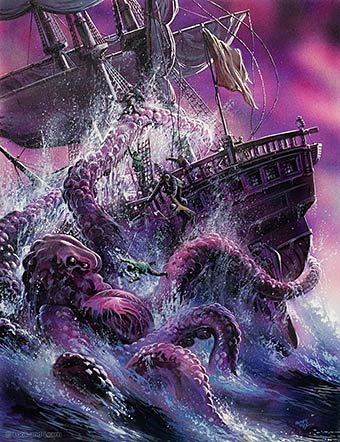

as Pliny the Elder. The much larger second type, the colossal octopus

(depicted in the above image), was reported to have attacked a sailing

vessel from Saint-Malo, off the coast of Angola.

Montfort

later dared more sensational claims. He proposed that ten British warships

that had mysteriously disappeared one night in 1782 must have been attacked

and sunk by giant octopuses. Unfortunately for Montfort, the British knew

what had happened to the ships, resulting in a disgraceful revelation for

Montfort. Pierre Dénys de Montfort’s career never recovered and he died

starving and poor in Paris around 1820 (Sjögren, 1980). In defense of

Pierre Dénys de Montfort, it should be noted that many of his sources for

the “kraken octopus” probably described the very real giant squid,

Archeteuthis, proven to exist in 1857.

In

1830, possibly aware of Pierre Dénys de Montfort’s work, Alfred Tennyson

published his popular poem “The Kraken” (essentially an irregular

sonnet), which disseminated Kraken in English with its long-standing

superfluous the. The poem, in its last three lines, also bears similarities

to the legend of Leviathan, a sea monster, who shall rise to the surface at

the end of days.