In

Greek mythology, Daedalus (Latin, also Hellenized Latin Daedalos, Greek Daidalos

(Δαίδαλος) meaning “cunning worker”,

and Etruscan Taitle) was a most skillful artificer, or craftsman, so skillful

that he was said to have invented images that seemed to move about. Daedalus had

two sons: Icarus and Iapyx, along with a nephew, whose name varies. He is first

mentioned by Homer as the creator of a wide dancing-ground for Ariadne. Homer

refers to Ariadne by her Cretan title, the “Lady of the Labyrinth”. The

Labyrinth on Crete in which the Minotaur (part man, part bull) was kept, was

also created by the artificer Daedalus. The story of the labyrinth is told where

Theseus is challenged to kill the Minotaur, finding his way with the help of

Ariadne’s thread.

Ignoring Homer, later writers envisaged the labyrinth as an edifice rather than a single path to the center and out again, and gave it numberless winding passages and turns that opened into one another, seeming to have neither beginning nor end (see labyrinth as opposed to maze). Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, suggests that Daedalus constructed the Labyrinth so cunningly that he himself could barely escape it after he built it. Daedalus built the labyrinth for King Minos, who needed it to imprison his wife’s son the Minotaur.

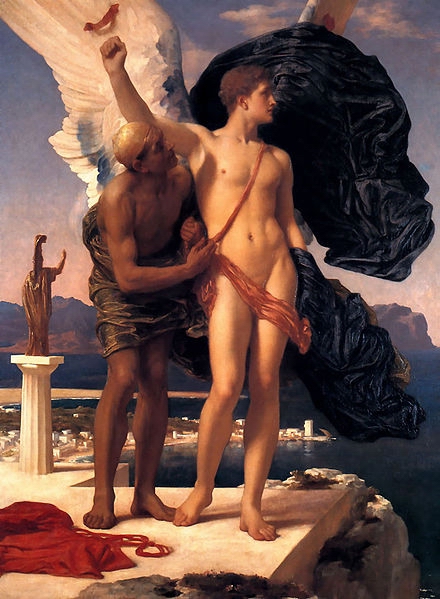

Daedalus

and Icarus, by Frederick, Lord Leighton, ca. 1869

The

story is told that Poseidon had given a white bull to Minos so that he might use

it as a sacrifice. Instead, Minos kept it for himself; and in revenge, Poseidon

made his wife lust for the bull. For Minos’ wife, Pasiphaë, Daedalus also

built the wooden cow so she could mate with the bull, for the Greeks imagined

the Minoan bull of the sun to be an actual, earthly bull.

Athenians

transferred Cretan Daedalus to make him Athenian-born, the grandson of the

ancient king Erechtheus, who fled to Crete, having killed his nephew. Over time,

other stories were told of Daedalus. In the nineteenth century, Thomas Bulfinch

combined these into a single synoptic view of material which Andrew Stewart

calls a “historically-intractable farrago of ‘evidence’, heavily tinged

with Athenian cultural chauvinism” (Stewart).